How 3 childless men wrote a parental leave policy

When Tom, Rob and Ben started CharlieHR, they wanted their parental leave policy to be better than the standard statutory requirements. The only problem? None of them had children.

Before Tom, Rob, and I started CharlieHR in 2015, everyone who had worked in our businesses had been a similar age. With Charlie, we hired much more intentionally for specific skill sets, experience, and seniority.

This, of course, included hiring parents. And as we did, we – three childless men – soon found ourselves confronted by a question we hadn't considered before. Did we have a strong policy for when a member of our team decides to become a parent?

After asking a lot of questions and doing a lot of research, we've built a policy that works for us, and we believe could work for other companies too. While we know that small companies don't have huge budgets, company size shouldn’t be a barrier to looking after your team.

Becoming a parent is a pivotal moment in anyone’s life. It's also often one of their most vulnerable moments – one where all of the emotions and pressures of having a child can coincide with worries about finances and work.

Taking care of your people when they’re in a situation is an excellent way to set yourself apart and build the foundation for a great company. Your business relies on their continued dedication and support – and in turn, they should be able to rely on the business when they need support.

The problem with parental leave in the UK

While working on early versions of our parental leave policy, we spent a lot of time talking with parents we knew and trusted. We wanted to know about their experiences with parental leave in the past, where the system succeeded, where it failed, and how they felt it could be improved.

A common theme of those conversations was flexibility: being able to take time off when you need it rather than all at once, being able to switch time off with your partner, being able to choose who stays home and who goes to work.

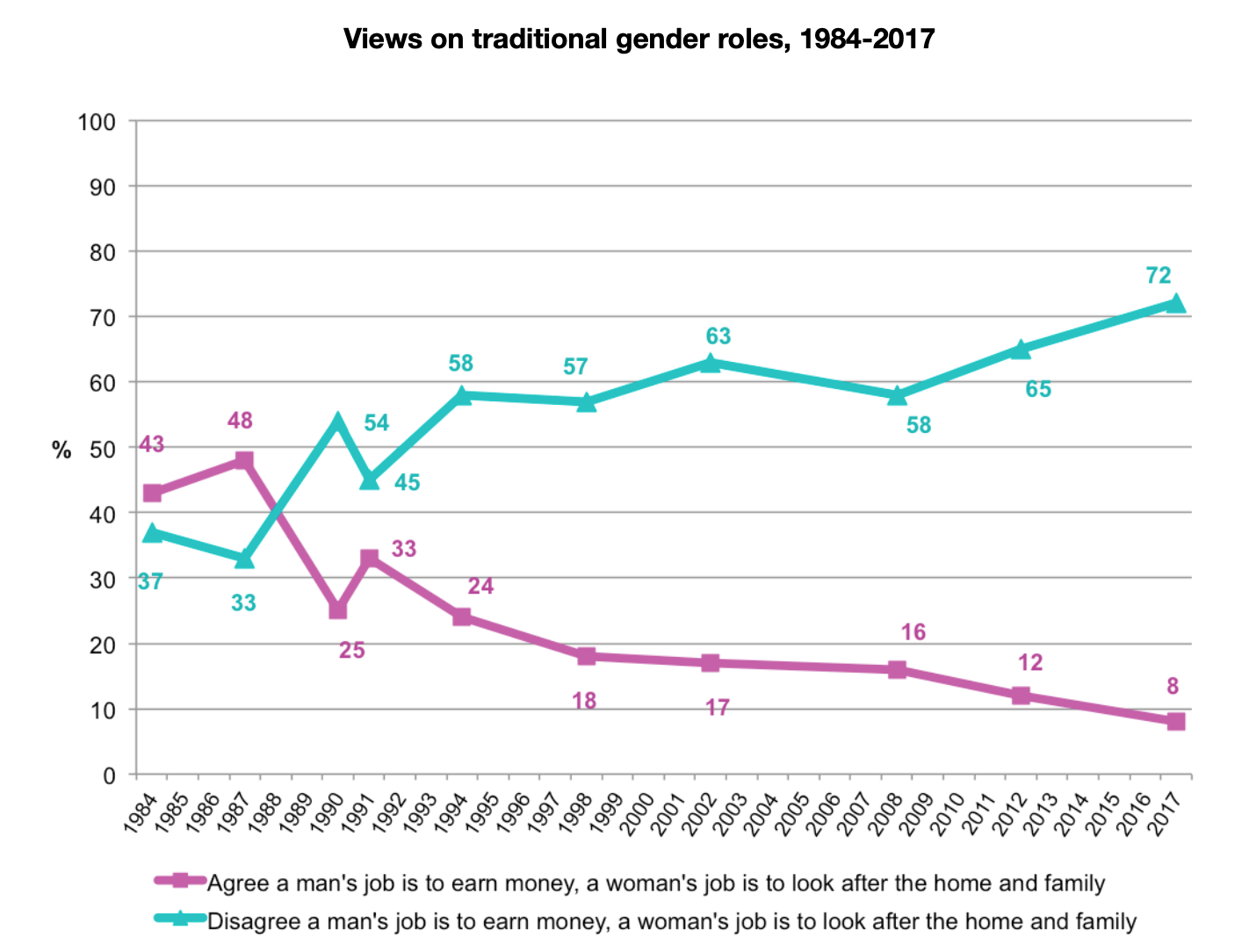

It's an idea that most would seem to share. A 2015 study found that a majority of parents believed that the responsibility for looking after children in a household should be shared equally. This fits into an ongoing change in views on gender roles – a 2017 study found that 72% of people disagreed with the statement "a man's job is to earn money, a woman's job is to look after the home and family" – a number which has been on an upwards trajectory for the last three decades.

In line with these changing views, the UK introduced Shared Parental Leave (SPL) in 2015. SPL allows parents to split up their total leave time into blocks and share those blocks of time with one another – such as by enabling one parent to go back to work for a time.

But participation in SPL hasn't reflected this change in views on gender roles. A government estimate suggested the take-up of shared parental leave could be as low as 2%.

The most common reason that families have reported not sharing their parental leave is financial. That's not too surprising. A pregnant woman who goes on leave in the UK is entitled to Statutory Maternity Pay, equivalent to 90% of their typical weekly earnings but only for the first six weeks. After that, they receive a reduced rate of just £145.18 a week (or 90% of their average weekly earnings, if that's lower). With Shared Parental Leave, their partners only ever receive that reduced rate: hardly a livable wage for most.

Meanwhile, despite changing public opinion on traditional gender roles, there are still many men who don’t feel comfortable using shared parental leave. There is a fear of jeopardising their position in the workplace or being on the receiving end of misogynistic stigma. Aside from those concerns, there are practical, administrative barriers that parents must negotiate before being able to participate in shared parental leave. The mother must sign off on the transference of leave days to their partner, (a requirement which enforces the outdated idea that the mother is and should always be the primary decision maker in the child-caring process) and parents are required to give at least eight weeks written notice of their leave dates.

This – alongside negotiating for flexible work or part time arrangements – can end up being such a challenge that some parents instead choose to simply quit their jobs.

Some businesses might see that as a good outcome, preferring to bring in a new employee rather than deal with the hassle of supporting one. For us, the idea that people would join our company, become a vital part of the team, and then quit because we couldn't support them in this pivotal and crucial time in their life – was totally absurd. It completely contradicted the ideals that we were building our company upon. And so we built our parental leave policy accordingly.

The CharlieHR parental leave policy

The main focus of our parental leave policy at CharlieHR is providing equal maternity and/or paternity leave, and giving both sets of parents choice and flexibility.

1. Flexible working hours for antenatal appointments

Throughout the pregnancy, we have flexible working hours for both mothers and fathers for antenatal appointments or classes.

Under UK law, if you're pregnant, you're entitled to take a “reasonable” amount of time off to attend antenatal appointments. Your partner can take time off for two appointments (lasting a maximum of 6.5 hours per appointment), but that time is unpaid.

The average pregnancy involves around 8-10 appointments – sometimes more, sometimes less – to check on the health of the baby, on the health of the mother, and on the progression of the pregnancy in general.

What we've found from doing research and talking to people is that any incentive against taking this time can lead to mothers (and fathers) skipping what could be critical appointments. Both for the health of the mother and to ensure that fathers can get equally involved in the pre-birth process, we chose to allow all of our employees who are pregnant or have pregnant partners to work flexible hours when those appointments come up.

2. Equal Benefits for Both Parents

We offer 6 weeks of fully paid leave, and another 6 weeks paid at 50%. All of this can be taken in blocks, apart from the first two weeks after the birth, where the mother must take time off in accordance with UK law. After this, our policy provides 14 weeks of maternity leave paid at 25% of their salary, or the statutory pay rate – whichever the higher amount is.

That is very different from the legal minimum requirement for both parents, but it's especially different for fathers.

Under the government’s default system, fathers using shared parental leave will only ever receive £145.18 per week (or 90% of their average weekly earnings, if that’s lower). If they don’t use shared parental leave, fathers get just two weeks of leave – at that same low rate of pay. Either way, they never get access to the higher rate of statutory pay that mothers receive for the first six weeks.

We built this part of the policy aiming to provide equal opportunities between parents to balance responsibilities as they see fit, rather than how circumstances permitted. We didn't want to force people into the choice so many parents in the UK have to make: having the other parent around, while taking unpaid leave, or having them absent, but earning enough to take care of the child.

3. Real control over parental leave

We created our policy to address the core concern that we heard time and time again from the parents we spoke to: they wanted flexibility and choice.

Offering choice is not just about making sure both parents can have the same type of leave and can choose to care for their child together. It’s also about providing the option to take this leave when most needed. Both the maternity and paternity leave that we offer can be taken in chunks with prior agreement.

This is one point where we felt we could really change the way parental leave worked: not one long, continuous leave but bits and pieces when needed most. This type of flexibility for mothers and fathers gives them options in the way they choose to take their leave.

The CharlieHR parental policy is our take on the level of support parents should have when starting or expanding a family. Yes, it was created by childless founders. But it was created by reaching out to a wide variety of parents, gaining their input, and then thoroughly considering the level of support that we would one day need if we decided to start a family.

The return on trust

Trust is a core tenet of our culture at CharlieHR. The best results are always found when there’s a high level of mutual trust between the business and the team. That also extends to how we think about parental leave.

Each family is different, and every set of parents is going to have different priorities for how they want to take care of their child in the weeks and months after birth. We trust our team members to make their own decisions about childcare, so we’ve made our policy as flexible as possible to allow them to do that.

That said, we realise this policy can't do everything. A truly parent-friendly culture is built by actions and attitudes as much as policy. Charlie's team and leadership need to reinforce our policy, each and every day – and we work hard at it. So far, our policy and approach to parental leave has worked well for us. We think it could work well for you too.

Learn more about HR policies and the essential HR policies for small businesses.